|

For

a larger photo click here.

Satan

Takes Over

Roger

Manley

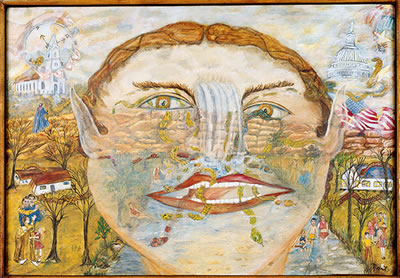

MYRTICE

WEST’S REMARKABLE PAINTING Satan Takes Over is perhaps

her most successful artwork to date, since it is one that satisfies

intellectually as well as spiritually and aesthetically. Its structure—a

huge, almost circular, semi-transparent face floating before a landscape

bisected by a stone wall and surrounded by a balanced assortment

of symbolic tableaux—is by several magnitudes her most graphically

memorable composition. At the same time, its narrative content neatly

sums up the key underlying messages of all her art with great economy

of means.

Most

of West’s other work utilizes a patchwork of perspectives,

focal points, and seemingly random events, which she deploys only

as if to cover as much informational territory as she can possibly

cram in. In Painting

#9, Song of Moses, for example, a single canvas includes

views of Jerusalem, the Sea of Galilee, and the vineyards where

the grapes of the land of Canaan (or of wrath) are being harvested

and then also separately trampled. Beyond these, the animal symbols

for the four Gospel saints mount steps leading up to the way of

the cross, which is revealed as the radiant door of heaven. This,

in turn, is surmounted by a rainbow and adjoins heaven itself, busy

with swarms of harp-playing angels, Jesus on his throne, and symbols

of the final judgment. And there’s more. Here and there she’s

filled in the gaps with images of the sanctified church, shepherds

guarding their flocks by night, both the seven-headed dragon and

the beast of the sea from Revelation, along with their familiar,

the whore of Babylon. If this weren’t already enough, right

in the middle of it all is what looks like a reference to the popular

gospel song “He’s Got the Whole World in His Hands,”

apparently led by an African-American preacher. Any remaining bits

of paintable surface are patterned with rays of light, swirling

clouds, or bolts of lightning.

While

it may be a fascinating work on its own terms, and certainly one

that invites an exploratory sort of examination, it shares the same

problem as many of West’s other paintings: filling up all

that vacui leaves no room for real horror—or, for that matter,

any other deep emotional response. None of them quite approaches

the unified coherence she accomplishes in Satan Takes Over

or resolves into any singular image as riveting as the cat-like

eyes of that huge, terrifyingly immediate face.

The

difference almost certainly has to do with how this particular painting

came about, compared to most of the others she has completed. Before

beginning her other works, West struggled to absorb passages of

Scripture and laboriously translated them into discrete images,

sentence by sentence. These she then seems to have simply arranged

around the painting surfaces wherever they might fit, while following

a few standard rules—such as keeping heaven toward the top,

earth toward the bottom, and so forth—but all the while maintaining

a basically flat field, lacking in extended visual depth. As a fundamentalist,

she is bound and committed to a word-for-word understanding and

retelling of the whole Scripture story. To edit—that is, to

leave out any details or substitute her personal experiences for

the standard accepted literal interpretations—would run counter

to the basic tenets of her faith.

Although

in hindsight West recognized certain relationships between what

she rendered in Satan Takes Over and various phrases and

images from the twelfth and thirteenth chapters of Revelation, this

painting does not directly repeat complete passages or images from

that book, except as disconnected phrases glimpsed only here and

there. At the time she painted it, West was deeply immersed in creating

a whole series of works based on this book of the Bible (and indeed,

painted on the reverse of this same work is one of her more typical

Revelations pieces). It should be no surprise, then, that there

might be some overlapping and mingling between the imagery constantly

on her waking mind and that in the Satan image. But instead of with

studying and reading, this painting began with another, much more

personal source: a frighteningly vivid dream, and one not described

by St. John, but all her own.

This

picture came from a nightmare. One night I woke myself screaming,

because I’d dreamed I was down by the creek (where I was baptized

when I was fourteen) and I saw this huge face. I saw myself sitting

down with my legs in the water while my daughter and someone I didn’t

recognize were in the water beyond me. Then things changed and I

recognized my daughter, and her own son and daughter, wading in

the creek up closer. I started hollering at them, and then I saw

the school children coming. And then in the face toward the back

I saw some people from my church. I realized they could not hear

me, and the water was full of snakes. I show how the water looked

just before it started. I also saw some other groups in the vision

but didn’t put them in. Some of them came into the water of

life too. I saw the head, and knew it was the Antichrist and we

couldn’t stop it, and nobody could hear me. Then in my vision

I started running toward the man in blue. I’d say he was John.

He climbed to the top, and I was with him. Then I woke up, and I

drew this mostly at night.

This

time West made no attempt to transcribe an extended narrative taken

directly from the Bible. For once, she found herself free to pare

down the imagery as much as she needed to (leaving out the “other

groups” she saw, for instance) to better capture the acute

feeling of the moment. It was a single, powerful, and above all

personal experience, related with as much directness as she could

muster. She wanted to communicate a startling encounter with her

own sense of real evil, and in order to do so, she needed quite

literally to face it head-on.

So I drew the home and family on the left side being taken away

by some sex family but they were not people. They were snakes. Then

there’s the Antichrist or Satan entering the school on the

right. You can also see the snakes as the beast or the Antichrist

getting into our government, and the flag and the stars falling.

Through the falling off, our government becomes satanic and turns

toward us as the old serpent, the devil, the great dragon and then

the church goes wrong. It gets on the wrong side, and gives its

service to the beast. Then God puts his hand on the time switch

of the end time.

Encapsulated in this one image is her concern for “the decline

of family values, the liberal ideas and practices allowed by the

church, the banning of prayer in the schools, and the corrupt government

that allows these tragedies to occur.”

|

Myrtice

West with

Satan Takes Over, 1994. |

Here

her fascination with apocalyptic “end times” (one shared

by most fellow believers, who hunt seriously through the meanings

they feel sure are embedded in Revelation) is grounded in her own

everyday world of family, community, and country. At the same time,

she questions the ordinary, outward appearance of things by contrasting

them against the ravenous but elusive face. Only she herself can

see it and sense the danger it implies, but while under the spell

of the dream, she is powerless to communicate her fears. Disturbingly,

she sees not only those she loves but herself behaving complacently

as well; rather than recoiling in horror, they each remain in dreamy

ignorance as the snakes writhe through the waters toward them. Meanwhile,

her “observing” consciousness, which is the same as

ours (i.e., that of ourselves as viewers of the painting), is looking

down upon the whole scene from some elevated height, seeing the

face and eventually realizing all it signifies. No one can hear

her warnings down below, not even herself, lolling by the river’s

edge. Instead, all she can do is watch herself living (as symbolized

by the lone leafy tree growing beside her) but as yet living without

full awareness, except for awareness of the end.

Therefore

listen: God’s hand is on the switch, and the clock has only

fifteen minutes left. But study again: Only one tree by the water

has leaves. I sat under it, with my feet in the water trying to

give or hold onto life in that final fifteen minutes, facing the

beast or Antichrist. The other trees behind the face are not clear

because Satan mixes up things.

To

Myrtice West’s way of thinking, the hand on the stopwatch

(or “switch”) isn’t the really threatening or

surprising element; God’s plan is only being played out according

to his own time-honored rules, presumably as laid out in Revelation.

All will come to an end, she believes, just as it was foretold it

would from the very beginning. Instead, she shows that the true

danger comes from letting Satan introduce confusion, so that one

is prevented from seeing or reaching the truth. Seemingly almost

intuitively, West utilizes a brilliant assortment of devices to

convey her message about the dangers generated by lies and deceptions.

The face, the clock, the leafless trees, the multi-colored snakes,

together with the falling stars, form a visual shorthand for the

threats of spiritual pollution, imminent destruction, and societal

collapse. No element is superfluous.

Had

she been content only to scatter these various symbols around as

usual, they might easily have competed confusingly with each other

and flattened their overall impact, the way they do in some of her

other works. This time, however, though West clearly saw her situation

outlined in an assortment of terrifying details, she succeeded in

expressing not only the feeling, but also the bigger meanings she

wanted to convey by arranging the components into a surprisingly

taut composition that suggests both depth and movement. She presents

a unified and nearly symmetrical formal structure, but one that

refuses to come to a standstill. It is an ingenious achievement.

The

scene (or, if one prefers, the “experience” of the dream)

takes place on three overlapping layers or planes, through which

one sees the whole image in depth. These can be understood dynamically

either as receding, if one’s eye follows the figure of St.

John (on the left, leaving the foreground to surmount the wall),

or else as projecting, if one follows the flow of water from its

origins in the distance and down its course back toward the lower

foreground.

The

background forms one of these planes, separated from the viewer

and the foreground by the dividing wall. This distant plane is presented

as an essentially symbolic place, containing as it does the church

(symbolizing religion), the stopwatch (time), the Capitol building

(government), the flag and falling stars (the nation), and the hand

(of God). Taken together, these elements show that West intends

the background to indicate the future, or, in other words, the realm

of both possibility and eventual outcome.

The

foreground is on another plane, which evokes the everyday world

of ordinary interaction and (somewhat idealized) daily life. For

West, it contains to some degree the past as well, since a few of

the figures are intended to represent her daughter, who stands near

the leafless trees. But for any viewer who has not previously heard

or read an explanation of who the individual figures are, the foreground

primarily indicates the present, or the realm of danger and choice.

The

giant face is presented as existing on yet a third, far more mysterious

plane all its own. The primary source of visual energy for the painting

stems from the difficulty one has in placing or keeping this plane

in any single static position. At times the face looms somewhere

near middle-depth in the scheme, with its eyes seeming almost to

rest atop the wall. But on second glance it appears to move forward

into the half-foreground, with its mouth spanning the creek and

the full width of the water passing between its lips. Then seen

yet again, it moves still closer to the foreground, even to the

very surface of the painting, staring back like the viewer’s

own bloated and distorted reflection. Looking at the painting, one

feels confronted and then, in fact, pursued. If the face alone weren’t

frightening enough, emerging from behind it and penetrating it—and

projecting still further forward from it toward us—are those

deadly snakes.

It’s

a masterful effect, but one that would risk pushing the image into

the exaggerated humor of ordinary caricature, were it not for the

way West uses water. The water functions to bind and unite all three

of these planes and keep them in balance by forming, together with

the wall, a foreshortened cross that extends back through the depth

of the whole  scene

into the distance. scene

into the distance.

The

water sustains the effect of the face and actually intensifies it,

by continually drawing it back toward the realm of symbol, only

to have it leap terrifyingly forward into the realm of actuality

again and again.

The

river is from the nightmare, and the waterfall is the water that

Christ offered, blocked by the Antichrist, that old serpent.

Like

Satan, the water of life also seems to emerge from the symbolic

plane lying behind the wall, then to approach and become tangible—tangible

enough in fact for one to wade in, or even be baptized in (remember

that West described this as the very creek where she herself was

baptized at age fourteen). But Satan blocks the view of its origin,

and thus in effect claims it as his own. He seeks to trick the viewer

with the illusion that it emanates from his own brow instead of

from Christ—the real source, according to Christian belief,

of everlasting life. Thus while Christ (as source) is actually the

central theme of this work, for Satan’s trick to seem effective,

Jesus must remain hidden and out of view.

In

order to escape Satan’s life-threatening deception, West argues

that one must follow the scriptural messages (manifest by the figure

of John) through their mysteries and beyond the difficulties that

keep one apart from understanding:

The

wall represents problems. We climb to try to understand what causes

these problems. The reason the head is so big is that when Satan

is in charge, he covers up everything before the final war and the

return of Christ. The earth is like God made it. We can see it,

but we can’t see what Satan does through the people. We have

to use our eyes, our noses, our mouths, and our ears that God gave

us to try to reach the interpretation with our conscious brain too.

Use them for God, or the serpent will change it all around.

Prolonged

experience with the painting’s pulsating cycle of threat,

followed and immediately countered by spiritual mastery, yields

a strong, visually-experienced message. Ultimately, it speaks of

enlightenment and understanding. Only by actively seeking truth,

and by bravely attempting to see through the confusing and deceptive

surfaces of things in the world, warns West, can one reach beyond

the dreamy illusions of life and finally begin the redemptive process

of fully waking up.

EPILOGUE

from Myrtice West’s Explanatory Letter

One

Sunday I started toward my church where me and my daughter were

both baptized, but somehow I wound up in a church twenty miles the

other way—a Holiness Church, where I’d never been before.

The Bible reading for that day was in Revelation. I apologized for

intruding and sat down. Then a woman stood up and said, “You-all

don’t know this woman, but I do. She is a Christian, and whatever

she sees, she can paint.”

Roger Manley was born in San

Antonio, Texas, and attended Davidson College in North Carolina

as an undergraduate. Later, after spending two years in the Australian

Outback living with a tribe of Aboriginals, he earned a graduate

degree in folklore at the University of North Carolina at Chapel

Hill. He is a photographer, folklorist, curator, and writer, with

areas of interest ranging from outsider artists and tribal peoples

to fairy tales and gardens. His books include Signs and Wonders:

Outsider Art Inside North Carolina (1989), which presents the

art of over 100 self-taught artists from North Carolina. He has

also co-authored several other books, including Self-Made Worlds

(1997), Tree of Life (1997), and The End is Near!

(1998). Manley lives in Durham, North Carolina and currently works

part-time as guest curator for the American Visionary Art Museum

in Baltimore and full-time as curator of exhibitions at the Gallery

of Art & Design, the art museum of North Carolina State University

in Raleigh.

Excerpted

from Wonders to Behold: The Visionary Art of Myrtice West.

Copyright © Mustang Publishing Company, Inc. Reproduced with

permission.

|