| The

Story of Myrtice West & the Revelations Series

Ann

Oppenhimer and Chuck Rosenak

LOCATED

IN THE FOOTHILLS of the Appalachian Mountains in a landscape of

waterfalls, streams, and lakes, Centre, Alabama was never part of

the romantic Gone with the Wind South. Myrtice Snead West,

who lives in Centre and is known to her friends as “Sissie,”

wears her graying hair up in a matronly manner and speaks with the

nasal, drawn-out twang of an elderly, rural white Alabaman. Like

the town of Centre, West has been bypassed by the “New South,”

but she has a unique voice and a remarkable tale to tell through

her art.

West

was isolated from most of her generation of Americans from the moment

of her birth on September 14, 1923, in Cherokee County, Alabama.

“There ain’t no cities in Cherokee. My Daddy had a farm

’way back on Spring Creek,” she says. “We went

on foot to church in McCord’s Crossroads. On one corner there

was a Baptist church; down the road were the Methodists. To keep

relatives happy [she had preachers of both denominations in the

family], we went to one church one week, t’othern the next.

We Baptists and Methodists grew up together. I’d call myself

a crossbreed—but now I’m a Baptist.”

The

big event of West’s youth was her baptism at age fourteen

in Spring Creek. Franklin Delano Roosevelt was president of the

United States; the Great Depression was a plague on the nation;

and World War II was a cloud on the horizon. In Atlanta, girls her

age were dancing the boogie-woogie, but West’s horizons were

limited by fundamentalist sermons, Bible readings, and small-farm

cotton prices. The answers to daily problems in her backwater world

were in the Bible and in prayer. Like Centre, the small town just

southwest of her birthplace, West was ill-prepared for the industrialization

of the South.

“When

I got old enough, I picked cotton,” she says. “I left

school during the war and married.” Wallace and Myrtice West

eventually settled on the Jordan farm on Cowan’s Creek. Later,

she would paint the ducks that swam peacefully in the creek beside

her house. “During World War II, I read the Bible straight

through four times,” she recalls. “My brothers, my husband,

my cousins were all overseas. Lots of them weren’t coming

back. We prayed a lot. You could hear them praying all over the

settlement.”

|

Wallace

and Myrtice West, circa 1942. |

In

time, the grueling, labor-intensive endeavor of harvesting cotton

became mechanized. Herbicides and machinery replaced hoe and picker.

Many who remained on the land in Cherokee County were bypassed by

progress and left without work.

Cotton

and tobacco usurped the forests that pioneer settlers found in northern

Alabama, and today the changing economic tide of rural Alabama continues

its advance. Modern factories march across the worn-out farms, and

mile after mile of dull rows of softwood pine are planted and harvested

like so many giant stalks of corn. New arrivals come from the North

to find jobs in plants sporting the logos of General Motors, Toyota,

and Mercedes-Benz. Many native southerners like Myrtice West have

been left with little more than their fundamental religious strengths.

But these are strong people, survivors whose rural hardships have

been replaced by urban hardships, and they have stories to tell.

The

man who once occupied the rambling, southern-style home in Centre,

once white and now peeling in the weather, moved farther south and

sold the house to the Wests in 1977. They feel fortunate to have

the house and the space for their extended family, which now includes

not only West's grandchildren, Kara and Bram, but also their spouses

and even a great-granddaughter. On the veranda, West hangs her cut-out

angels to sell to visitors. When a breeze blows, they fall from

their coat-hanger hooks onto the plank floor. “They’s

fallen angels,” she explains with a laugh, while resurrecting

them with a stepladder kept on the porch.

[Editor’s

note: The house described above burned to the ground in February,

2000, along with most of the West’s possessions. No one was

injured, and the family has moved to another house in Centre.]

West

started to paint in 1952, about the time of her second miscarriage.

“Before, I never thought of art,” she says. “After

my miscarriage, all I wanted to do was lie on the floor and draw

pictures of Christ. It was like the hand of God directing me.”

But, even before this time of trouble, her artistic endeavor had

begun. When she was just a child picking cotton in the fields, West

says, “I was always bad to collect pictures and make things.”

For years, she drew pictures of rural scenes, riverboats, animals,

flowers, a few angels. Many of these bucolic renderings still hang

on the crowded walls of her home.

Her

husband Wallace had been taking photographs of “weddings and

ballgames and such.” He had started with a simple Brownie

camera, and Myrtice took a correspondence course to learn how to

hand-color photographs. By adding color to her husband’s pictures,

she could make them more attractive to buyers.

Her

tinted photographs may have brought in some needed funds, but they

were not art. Her early paintings found a local market, but they

were not art. The painted gourds with religious scenes on them and

the cut-out angels, which she still occasionally makes, are colorful

and charming, but they are not art. It took West many years to find

her voice and sing her own song. West’s early works were copies

of genre paintings, postcards, and pictures, both secular and religious,

taken from books and from memory. “When I started,”

she explains, “I didn’t know about brushes nor colors.

I couldn’t even hold a brush!” West painstakingly taught

herself a craft, which became an essential ingredient for the art

that was to follow.

|

Wallace,

Myrtice, and Martha Jane West, circa 1963. Myrtice hand-colored

this photograph, a craft she practiced for many years. |

Like

many other folk and self-taught artists, Myrtice West had a decisive

moment in her life, a sudden traumatic experience that left her

a different person. Her life pivots on the story of her daughter

Martha Jane, and her words spill out in a torrent as she tells how

the little girl, the child she tried so hard to conceive after two

miscarriages and a tumor, was born in 1956. “I thought she

was our miracle, our gift from God.” Just three decades later,

however, Martha Jane, a young mother of two children, would be murdered

by her ex-husband Brett Barnett. It was a classic case of spousal

abuse, and although West’s rambling conversation touches on

many subjects, she always comes back to the story of Martha Jane’s

death.

West

says she had a premonition that something bad would happen to her

daughter and grandchildren. When the young family left in 1977 for

Japan, where Barnett was stationed with the Air Force, she wrote,

“When I watched them leave that day, my heart was breaking.”

For comfort and solace, she turned to painting religious pictures.

She first attempted a

large painting of Christ ascending into heaven, which she intended

as a gift to her grandson Bram. She was so pleased with the results

that she became inspired to illustrate the New Testament book of

Revelation. In the same way that reading the Bible had helped West

survive her fears during World War II, reading and interpreting

Revelation helped her survive the chronic worry over her family’s

well-being.

“I

knew her husband was a mean man,” she says. “He’d

lock my grandson in his room for weeks at a time. He chewed up tobacco

and made the boy drink the juice. That day, I got a feeling we should

go to Birmingham [where Martha Jane and her children were living].

It was 1986 when the killing happened; Bram was twelve.” A

decade later, West’s emotions are as fragile as the day she

learned that Martha Jane had been shot by Brett Barnett, who is

now in prison with a life sentence. West worries that Barnett might

be paroled. “He will kill again,” she says. “He’s

low-down mean.”

West

began work on the Revelations Series in early 1978 when she first

became obsessed with her daughter’s unhappy family life. After

Martha Jane and the children left for Japan, West’s grief

continued to mount. Her sorrow went beyond her capability to imagine,

beyond anything she had a right to expect from a loving God. The

solution to her grief, the answer to her problems—and comprehension

of the ensuing tragedy—came from the Bible. Night after night

she sat alone with her cup of coffee. She read the Bible at the

plank-board table in the kitchen. Two o’clock. Three o’clock.

Four o’clock. In the company of the noises of sleepers and

the creaking of the old house, she sat alone studying the Bible.

In time, solutions to the mystery of God’s will appeared to

her. “I saw Revelations in flashes,” she says. “Whether

it was through my eyes, God’s eyes, or St. John’s eyes,

I’m not sure. But the hand of God directed me to put it down.”

Painting

the book of Revelation became a way for West to work through her

anguish. The undertaking meant reading and re-reading the twenty-two

chapters of the last—and to many scholars, most difficult

and bizarre—book of the Bible. Not only did West intend to

make paintings that would explain the obscure and mystical Scripture,

but she also set herself the task of illuminating the text almost

verse by verse. Over the next twenty years, painting would become

her self-taught form of therapy, a way of coping with an unspeakable

crime and the loss of her only child.

In

1983, West self-published a 47-page booklet, The Book of Revelation

in Spirit and Vision. In the book, she explained that the Revelations

paintings, like her writing, were inspired by God. “I sat

here sometime late, probably after midnight. Starting on this book

as I started on my pictures—unless you enter into the Spirit

you probably can’t believe this—but Christ now has drawn

a curtain, and I can’t remember how I drew them. I felt as

if someone else held the brush when I painted them, and now it is

as if someone else holds the pencil as I write.”

Over

a period of seven years, working mostly in the early morning hours,

West “put down” the paintings as, she believes, God

directed. She first worked in pencil to draw the figures, and then

gave them a light coating of paint made from dry powder mixed with

water so the lines would show through but not smear. After this

she “came in with the oils,” often using both acrylic

and oil paint for the layers of color. “It took me three months

to put each one down and three months to paint it,” West says

about the thirteen paintings. On three of the pieces, she painted

on both sides of single sheets of plywood. Others were painted on

cloth “couch covers” stretched over window-screen frames,

which West purchased from someone who came by her house with a truckload

of screens. She bought them thinking she would find a use for them

eventually.

Born

in anxiety, the Revelations Series became West’s passion.

“You keep the paintings on your mind instead of your troubles,”

she explains. They have the essential ingredients of great folk

art: a fearless creative and personal vision that is both universal

and intimate. Her paintings gave her a chance to impose order, structure,

and certainty in a life suddenly consumed with confusion—and

in a world in which it seemed that God had disappeared. In art,

West found a remedy to heal her life and a song to connect with

the wide world that had bypassed Centre, Alabama.

“Putting

down” some of the characters in Revelation “was easy,”

she says. “I knew what the angels looked like from my illustrated

Bible. Adam I got from that chapel across the seas [the Sistine

Chapel]. God and Adam is whiter than white—more beautiful

than I can make ’em.” So there were elements of earlier

art in the work, some that would be considered trite to a trained

artist: winged angels in white robes, cartoonish animals, etc. The

rest—the composition, colors, dimensions, and biblical references

and characters that weren’t to be found in illustrations—she

had to “work out” for herself, find her own artistic

voice, and, as she would say, let God direct her brushes as she

made the thousands of choices every artist must make to complete

a piece.

|

Myrtice

West in the back hall of her home in

1993, surrounded by her Revelations Series

and other paintings. |

For

several years after completing the series, West refused to sell

the Revelations paintings, although she had offers and a need for

income. However, the work represented seven years of anguish, and

she felt the series should remain together, rather than be sold

off individually and scattered across the country. Eventually, an

Alabama folk art dealer persuaded her to paint a copy of each painting

in the series; the dealer said she would sell the copies and take

a percentage. These copies became known as the “Second Set”

of the Revelations Series, and, while fascinating compared to much

contemporary folk art, they are clearly inferior to the originals.

As West explains, “I did the Second Set in less than a year,

so I could sell them. Anyone can tell the difference; they just

ain’t that good.” It took many years for the Second

Set paintings to sell, and West now regrets the time she lost making

copies rather than creating new works. From 1993 to 1998, West again

became inspired and completed two multi-painting series, one depicting

the book of Ezekiel, another Daniel. As of this writing, she is

working on a series of paintings from Zechariah.

In

the late summer of 1992, Rollin Riggs, a Memphis businessman, journalist,

and occasional folk art collector, decided to break up his drive

from Atlanta with a visit to West’s home. He had visited several

artists between Memphis and Atlanta—Jimmy Lee Sudduth, Howard

Finster, Fred Webster, B.F. Perkins, Burgess Dulaney—and had

become charmed by both the art and the artists. When he arrived

in Centre, he stopped at the Pump House, the small gas station at

the intersection of Routes 9 and 411, and asked the cashier if he

knew Myrtice West. He gave Riggs directions to the West’s

home a few blocks away, telling him to look for the house with the

big painting of Jesus on the front porch.

When

Riggs entered West’s home, he knew his life had changed. In

the hallway, he saw the breathtaking tableau of all the Revelations

paintings hanging along the walls. Scattered throughout the house,

he found painting after painting that he knew was extraordinary—and

almost unknown to the burgeoning folk art world. He offered to buy

the original Satan Takes Over,

but, as always, West wouldn’t sell. Instead, he bought its

Second Set version and eight other religious

paintings. According to West, Riggs was “an angel sent by

God,” and his check for the nine paintings prevented the imminent

repossession of the family van.

Over

the next year, Riggs visited West numerous times, sometimes buying

art but mostly befriending, counseling, and documenting the artist.

Increasing numbers of collectors and dealers were finding their

way to Centre and making sometimes complicated proposals to West:

consignment deals, licensing offers, and such. As Riggs helped West

with her business and personal questions, he became convinced that

the Revelations Series was an extraordinary body of art that also

represented a certain type of 20th-century Southerner who was vanishing

with age and the pervasive mass media. He thought there might be

a book in it, and he worried that the paintings were unprotected

from fire and theft.

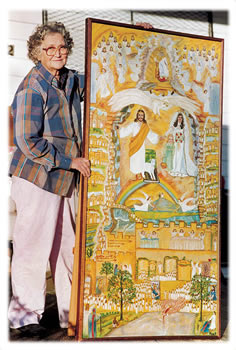

|

Myrtice

West with

Christ and Bride Coming into Wedding. |

In

the fall of 1993, as her grandson prepared to go to college, West

decided it was time to sell the Revelations Series. She had come

to like and trust Riggs and several other folk art dealers, and,

at Riggs’ urging, she hired a lawyer in Rome, Georgia to represent

her in the sale of the paintings. Riggs submitted the best bid for

the Series, which included cash and “best efforts” clauses

to keep the paintings together and to publish a book on them and

West. In late 1993, Riggs hired a videographer to document the paintings

in the West's home, and then he loaded them into a van and drove

them to Memphis. West dashed to the bank to deposit his check and

pay off her mortgage, and then she went back to work on her new

Ezekiel Series.

In

The Book of Revelation in Spirit and Vision, a determined

woman with only an eighth-grade education presents a detailed analysis

of the first four chapters of Revelation. She carefully dissects

the sentences of each verse and applies their teachings to her art

and life in the hope of getting God’s message out. “There

is an unseen hand in this work,” she writes. “As I take

my pen in hand, I know also I am not a writer and unless Christ

comes in, I’m afraid I can’t explain how I did these

pictures or why.” Ultimately, the job of interpreting the

entire book of Revelation proved to be too much for her, and she

completed the visionary Revelations paintings instead.

West

is delighted that a group of writers studied her paintings in order

to make a book about them. “When Rollin said that he was going

to get people to write about each of my paintings, I felt like God

had sent him.” She especially likes the fact that each writer

has written in his or her own way—some perusing and reflecting

on a painting, others making personal or telephone interviews. One

writer even sent her twelve pages of questions to answer about a

painting. She is glad that all the contributors were exposed to

St. John’s writings and his revelatory message, just like

the people who will read this book and see her paintings. “This

way, so many others will get inspiration. This is what God wanted,”

she says.

Myrtice

West has turned the fire and brimstone of her anger into paintings

that erupt with vengeance—and promise glory for those who

believe in Christ. She has sublimated her anguished memories into

paintings that preach from the depths of her distressed soul. She

slays her dragons pictorially, and she keeps her daughter’s

memory alive with her paintings. West is an evangelist in paint

who hopes to help others at the same time she helps herself. She

easily slips into a rambling sermon that mixes biblical quotations

with the jargon of a television evangelist, and she defends her

use of images as an aid to religious teaching.

Despite

her troubles and her religious zeal, West is a vivacious, friendly,

energetic woman. She tends a yard full of flowers and cats, cooks

for her husband Wallace (“who has had cancer eight times”),

her grandchildren and their friends, and, after raising her two

grandchildren and nursing her mother (who died in 1996), is now

the matriarch of an extended family of seven who either live with

her and Wallace or nearby. She’s a woman who has worked hard

and looked after the needs of others all her life.

|

Wallace

and Myrtice West, 2003. |

It

takes time to evaluate a work of art and the oeuvre of an artist. Myrtice West is not alone in painting

her dreams and religious visions, and she is one of several self-taught

artists in the late 20th century who see their paintings as a means

of spreading the gospel and warning the world of a coming Apocalypse.

But the Revelations Series of Myrtice West has already made a huge

contribution to the field of visionary art, and her passion has

made an enormous difference in the lives of Rollin Riggs, Carol

Crown, the essayists in this book, and all those who have met her

and studied her paintings. West’s song, which was “put

down at her eatin’ table” in the middle of the night—without

hope of recognition, amid desperation and violence—is being

heard at last.

Ann F. Oppenhimer has a B.S.

degree from the University of Richmond and an M.A. degree from Virginia

Commonwealth University. For 17 years, she taught art history at

the University of Richmond, where she was curator of Sermons

in Paint: A Howard Finster Folk Art Festival, one of the first

university exhibitions of Finster’s work. In 1987, she and

her husband, William Oppenhimer, founded the Folk Art Society of

America, a national organization for the discovery, exhibition,

study, and preservation of folk art. She currently serves as president

of the Folk Art Society of America and is publisher of the quarterly

magazine, Folk Art Messenger.

Chuck

Rosenak, attorney, author, and recognized American folk

art expert, has made collecting a second career and fashioned a

New Mexico lifestyle devoted to finding and promoting the best self-taught

artists working in the United States. With his wife Jan, Rosenak

has authored the authoritative Museum of American Folk Art Encyclopedia

of Twentieth Century American Folk Art and Artists (1990),

as well as Navajo Folk Art: The People Speak (1994), Contemporary

American Folk Art: A Collector’s Guide (1996), and Saint

Makers: Contemporary Santeras y Santeros (1998). In 1999, the

Rosenaks donated their extensive research files to the Archives

of American Art in Washington, D.C.

Excerpted from Wonders to Behold: The Visionary Art

of Myrtice West. Copyright © Mustang Publishing Company,

Inc. Reproduced with permission.

|